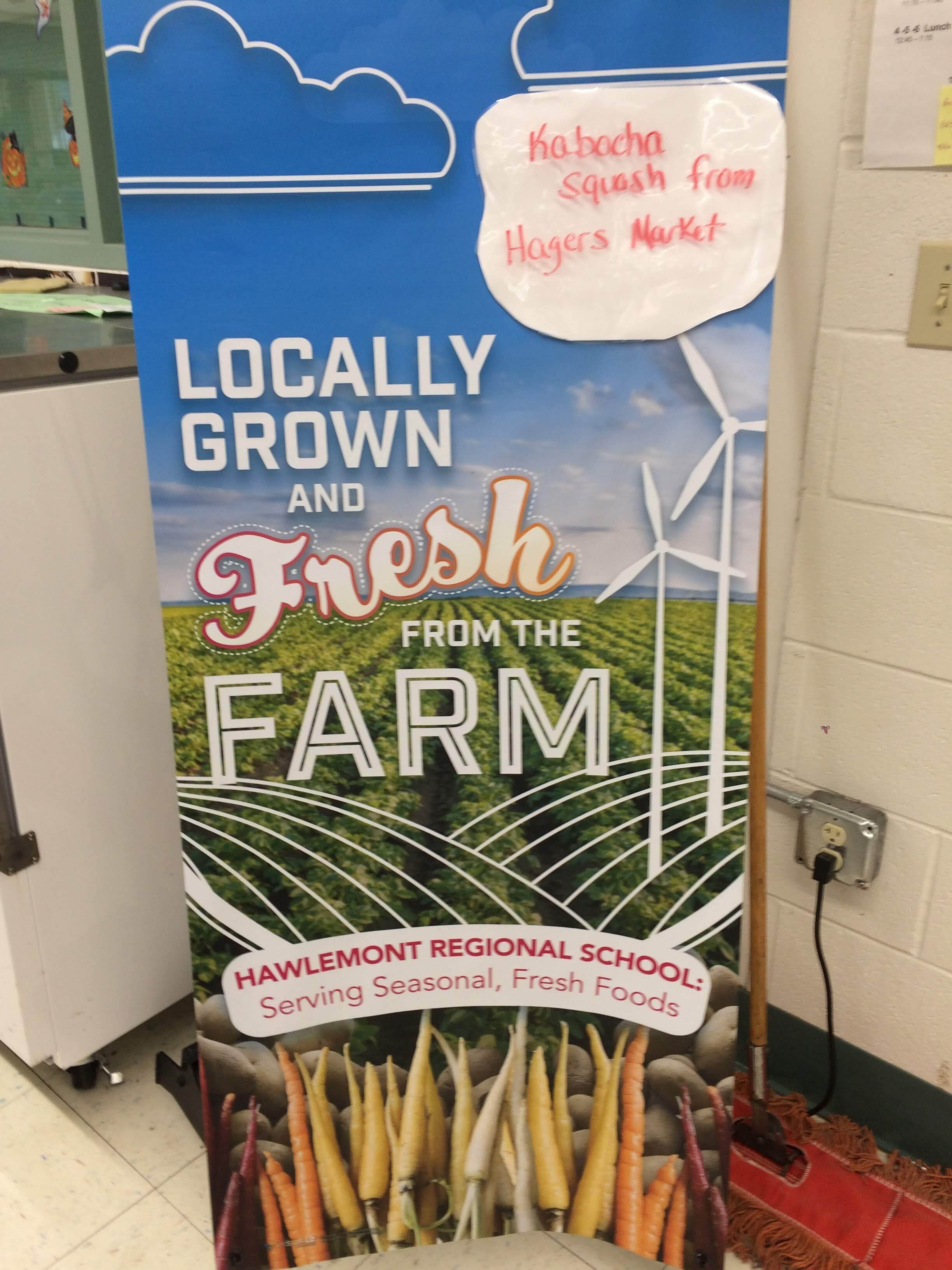

Central Elementary School (CES) recently closed out a phenomenal year of Farm to School (FTS) programming, wrapping up 12 months of work dedicated to advancing food education at the Bellows Falls area school.

Selected as a participant school for the 2021-2022 Shelburne Farms Northeast Farm to School Institute, CES won a $5000 grant to jumpstart their FTS programming. While the school already had a garden and dedicated food service staff, the funding and coaching provided by the Institute helped to formalize the FTS program and integrate it more fully into the school culture and environment.

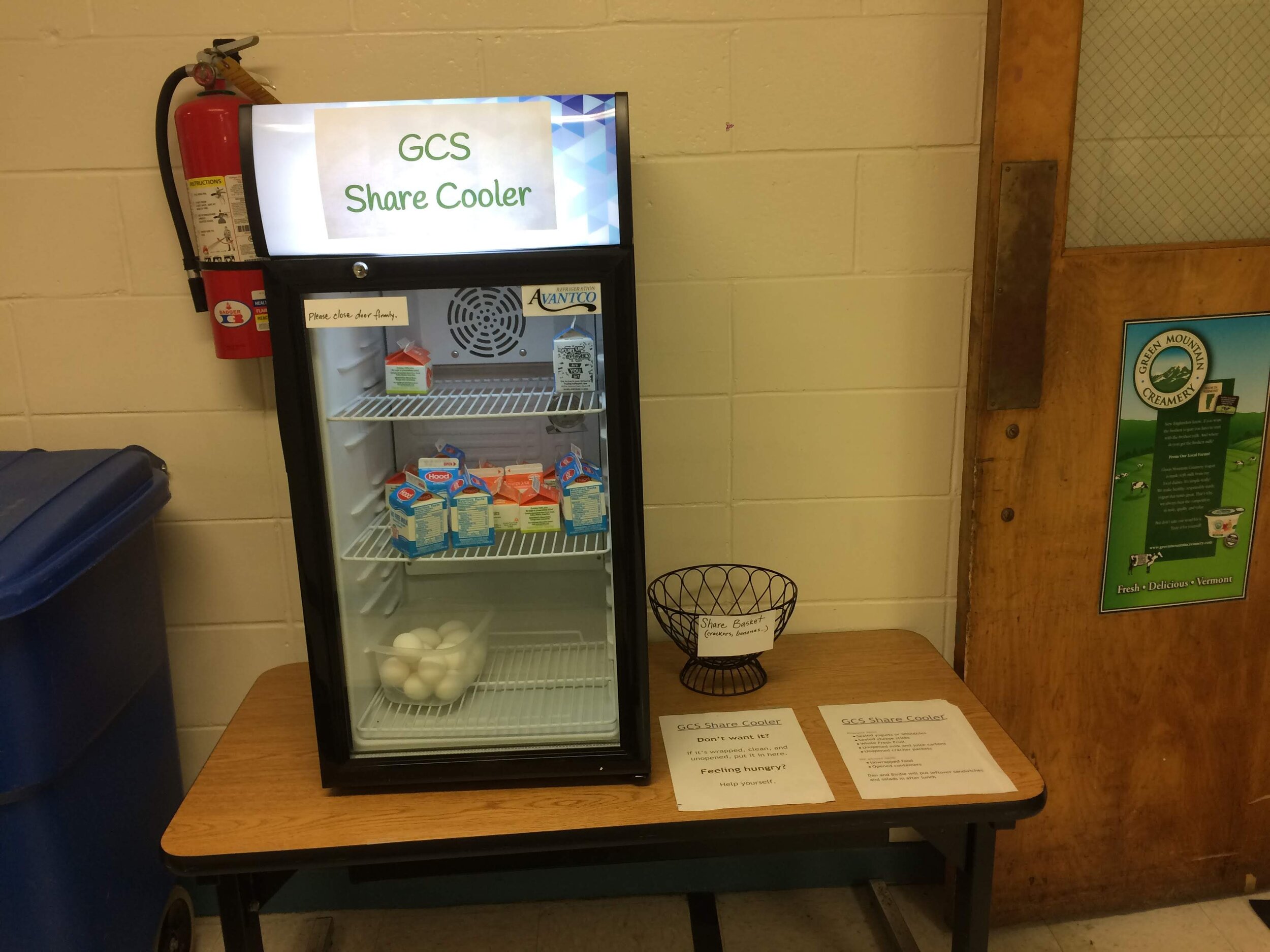

A thriving Farm to School program usually involves three key components: the classroom, the cafeteria, and the community. Often, it takes years for a school to be active in these areas, but Central’s team has grown its program from the beginning and has a comprehensive program that reaches into each of these areas.

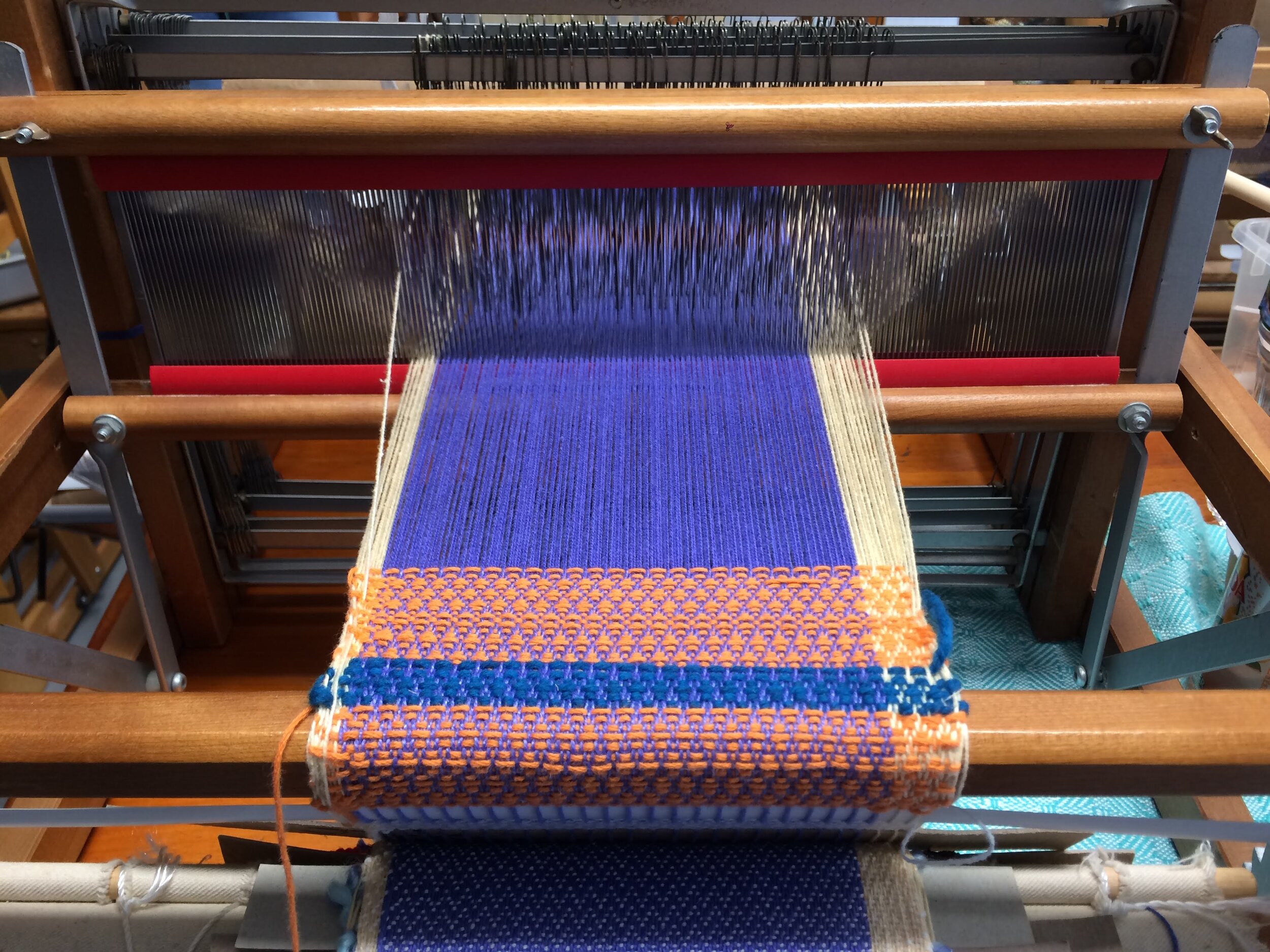

In the classroom, Farm to School came alive in the 2nd-grade classrooms. Teachers Kate Kane and Judy Verespy worked closely with librarian Jody Hauser to devise monthly programming that included everything from art projects and read-alouds to food preparation and tastings.

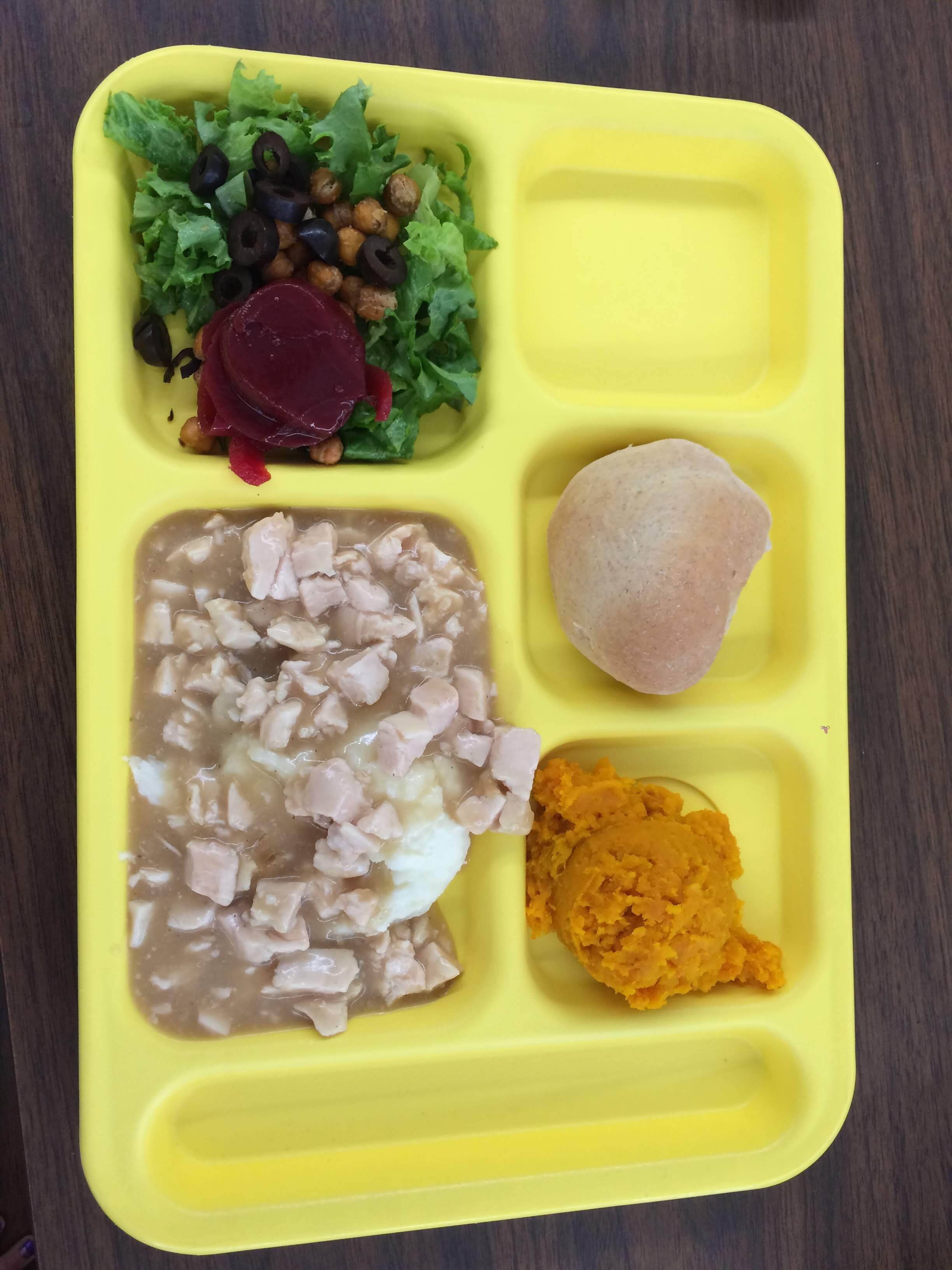

In October, students harvested carrots from the garden, painted carrots with watercolors, and made informational posters about carrots before teaching other classrooms what they’d learned. Food Service Director/Garden Coordinator Erica Frank baked delicious carrot muffins for the entire school. In January, students painted with beet juice and made beet hummus in the classroom. Erica, again tying in the cafeteria, made nutritious and delicious beet brownies for the school food program.

The third “C” of successful FTS programs is community, and Central Elementary was able to connect with its community in impressive and innovative ways. In March, when the Harvest of the Month was maple syrup, the students visited a neighborhood home that ran a sugaring operation! They also tasted some “sugar on snow” made by a local (teacher’s!) family. In the spring, local farmers John and Teresa Janiszyn of Pete’s Farm Stand in Walpole, NH, visited the classroom. The farmers taught students about soil and composting, and students planted cucumber seeds. Weeks later, they transplanted these same cucumbers into the fields at Pete’s! What an amazing circular connection between students and the farmers in their communities. It has been a mutually beneficial relationship between the community and Central Elementary this school year, with each gaining and giving benefits to the other. The Rotary Club of Bellows Falls came to help with a Garden Volunteer Day and donated garden supplies. Students received gift cards to buy something at Pete’s, funded by the FTS budget.

Central’s story is one of success, but it’s only the beginning of their journey, and it has been possible through many dedicated staff members and community support. The Institute helped the team shape an action plan for their program. Principal Kerry Kenedy has supported FTS from the beginning and plans to integrate the program more deeply into the school culture over the years. One step in this process is that next year, the third grade will join the second grade in receiving monthly programming. Physical Education teacher Peter Lawry was integral in planning, building, and maintaining the garden. And Erica Frank has worked to connect the summer school program to the FTS activities throughout the summer.

If you’re curious about all the amazing things Central has been up to, please check out the inspiring book Librarian Jody Hauser made with the students.