The Common Bean is back with more harvest updates! Read on for fun stories from Oak Grove School Garden Coordinator Tobi Buchman in editions 4–6. We’re happy to spotlight this newsletter as a great example of Farm to School programming in action, connecting students to food, gardening, and community.

Brattleboro Union High School Farm Club Officially Joins 4-H

Every other Tuesday, Brattleboro Union High School (BUHS) students meet during ACE block to participate in Farm Club, an in-school club dedicated to exploring students’ connection to the local food system. This is the second year of Farm Club’s existence, made possible through a four-year University of Vermont (UVM) Extension 4-H grant called Youth Innovators Empowering Agriculture across America (YEA), funded by the USDA. There are four other projects in New England funded by this grant, all focusing on improving access to 4-H experiential learning opportunities.

In the spirit of the 4-H partnership with BUHS, Farm Club became an official Windham County 4-H club during their November meeting. 4-H programming includes a community of more than 100 public universities across the nation. 4-H and Land-grant University Extension services provide resources and experiences where young people learn by doing. Through 4-H, youth complete hands-on projects in areas such as health, science, agriculture, and civic engagement, in a positive environment where they receive guidance from mentors and are encouraged to take on proactive leadership roles. Youth experience 4-H through in-school and after-school programs, community clubs, independent study, special interest groups, and 4-H camps. BUHS’s Farm Club is one of the few in-school clubs in Vermont, making it a pilot for other schools’ participation.

Students filled out the official 4-H charter, where they chose a name for the club, the “Green Paws,” and will enroll in the 4-H Z-Suite system, allowing students to access the many opportunities now available through the greater UVM 4-H network. Excitement brewed when club members learned that they could run for leadership roles as a 4-H club, such as president, vice president, treasurer, and secretary. Teen leadership is one avenue where students will gain life skills that will prepare them for journeys beyond school and 4-H.

The “Green Paws” are led by Windham Windsor County 4-H Educator, Camille Kauffman, and school para-professional, Paula Kettle. Farm to School Coach Adelaide Petrov-Yoo of Food Connects is also a key partner in club activities, leading monthly Harvest of the Month Taste Tests. So far, the club has conducted bell pepper and apple variety taste tests. Partnering with Food Connects integrates the club into Brattleboro’s wider community food culture.

4-H is grounded in the research-backed principles of Positive Youth Development, including sparking curiosity and inspiration, deepening community engagement, fostering a sense of belonging, and building meaningful connections between youth, caring adults, and their communities. Farm Club provides an ideal setting for 4-H, and the Green Paws look forward to the many ways they can expand their horizons by joining the network of four-leaf clovers.

View this infographic for more ways that Farm Club has launched and grown in the past year.

Written by Camille Kauffman

The Common Bean Editions 1-3

The Common Bean is a new publication from Oak Grove School Garden Coordinator Tobi Buchman, featuring fun updates and stories from the school garden. Check out editions 1–3 below!

Edition 1

10 Reasons Why You Should Sign Up for a Food Related BEAMS Program

Brattleboro Area Middle School offers afterschool programming for all enrolled students through its BEAMS sessions (Brattleboro Enrichment Activities for Middle School). The first session of BEAMS will run Sept.15 - Oct. 24, 2025. Check out the course schedule.

As a Farm to School Coach, I know it’s important to expose students to education about our food systems. This includes cooking food, learning about where our food comes from, and how this all affects our communities and ourselves. When students learn about food, they can make informed choices that affect our bodies, our land, our economy, and our communities. A fun way to learn about food is through cooking and eating it. That is why I recommend trying a food-related BEAMS program this year.

10 reasons WHY you should sign up for a food-related BEAMS program:

Cooking classes tend to be the most popular club choices.

Students love them, many joining repeatedly over the course of the year! Ms. Gao’s Chinese Cooking club and Ms. Goodhue’s Cooking club always fill up fast, so sign up early.

There are many cooking club choices offered several different days of the week, so you can find one that fits your interests or your schedule.

BEAMS programs run the gamut; from Grilling club to Harry Potter Cooking. The latter offers a chance to consider what you enjoyed most about the story and characters, bringing it to life with food and baked treats grounded in the story itself.

Bring home a huge bag of gifts from the Holiday Cookie Swap.

Students contribute recipes connected to their own family traditions. Over six weeks, students make, bake, and freeze the holiday treats.

On the final day, students have the opportunity to take home a plethora of different treats that they can gift to others. It’s pretty magical to watch this culminating event each year.

Hang out with your friends outdoors during Grilling Club.

Nick Yileadis, BEAMS director, remembers seeing a group of students gathered together around the grill, laughing and chatting with each other as they learned grilling techniques.

He felt “as if we were peering out on a neighborhood barbecue… such a great example of how food-based experiences can draw students together socially”.

Learn new skills, gain new confidence!

Cooking is truly a lifelong skill. Students hone these skills in BEAMS, and then recreate these dishes at home and throughout their lives.

Even clubs like Pizza Friday or Ramen Cooking offer a spin on this, showing students over six weeks how to confidently prepare a foundational recipe while also demonstrating how a few simple tweaks or different ingredients can bring variety to a common meal.

Explore other cultures.

Ms. Gao’s Cooking Club shares Chinese culture with students. Food is an engaging, hands on, and delicious way to give students a window into another culture.

Tap into your artistic side with food as the canvas.

Baking clubs allow students to decorate a cupcake and then present their design to their peers. This also helps build confidence and communication skills.

Explore a potential career path.

One former BEAMS student, passionate about cooking, participated in just about every cooking club offered by BEAMS. He also offered recipe ideas and program themes to club leaders.

This year, he is pursuing an opportunity to do an internship and kitchen work with The Vermont Table.

BEAMS allowed this student to explore his interests and practice leadership skills. He is now continuing to follow his dreams as he advances in his education.

Drink some tea and chill out.

Join Ms. Carmichael’s Tea Talks to drink some tea and decompress from the week.

You may be surprised to see that simply gathering around tea can build community and open up conversations.

Eat delicious food each week.

Ok, that one is obvious but it’s still a great reason to join a BEAMS cooking club!

Written by Adelaide Petrov-Yoo

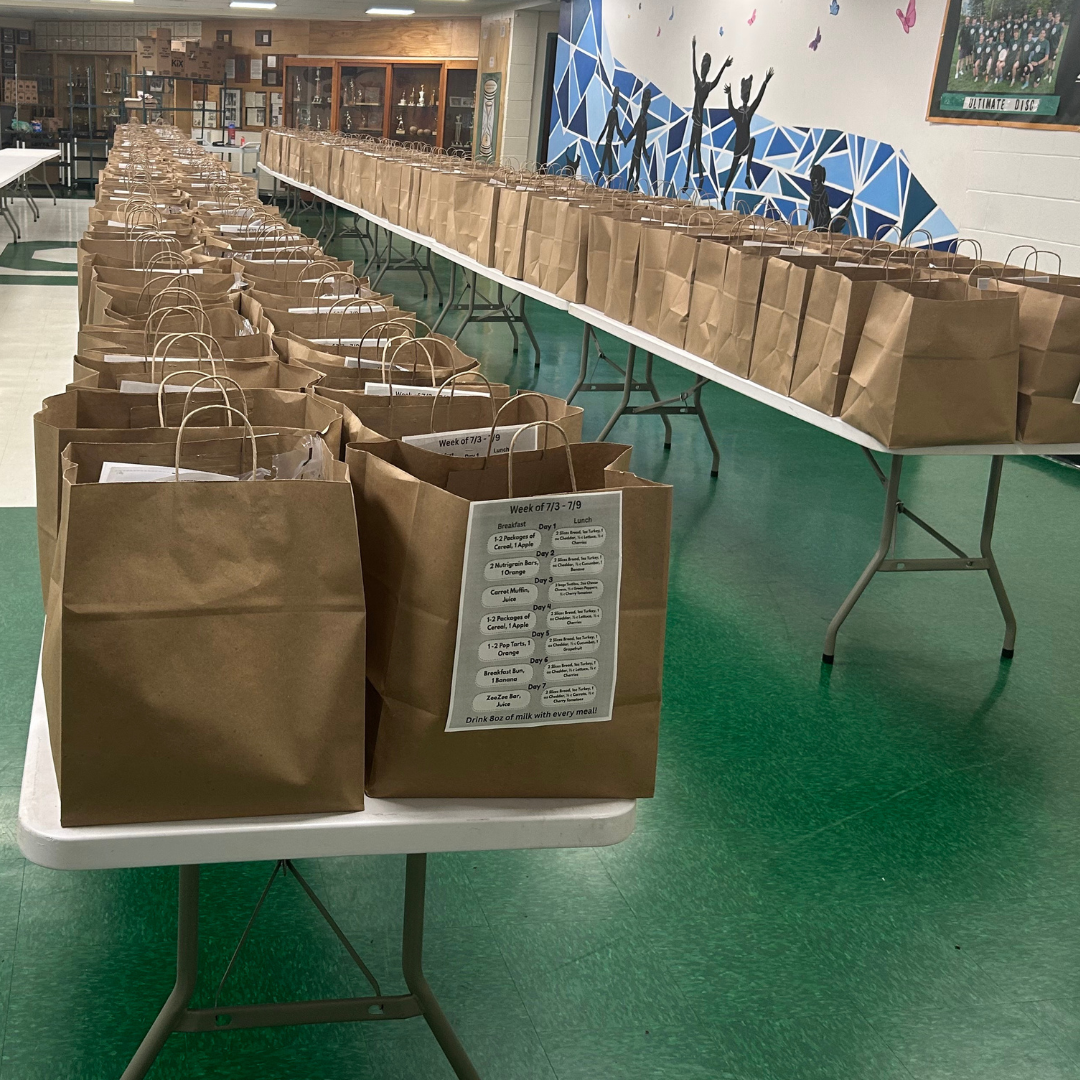

Summer Meal Kits in Full Swing Across Windham County

It’s been a busy summer in Windham County, and there’s still a month to go! Across the region, teams from Windham Northeast Supervisory Union (WNESU), Windham Southeast Supervisory Union (WSESU), and West River Education District (WRED) have been hard at work assembling and distributing free summer meal kits for kids and teens.

These kits have included products from local producers like Cabot Creamery, Miller Farm, Vermont Bean Crafters, Mi Terra Tortilla, All Souls Tortilla, and The Bread Shed. These kits represent community effort rooted in local support.

It’s not too late to participate. Meal kits are still available for children and teens up to age 18 throughout August. Each district has its own schedule and pick-up locations, so be sure to check with your school or supervisory union for the most up-to-date details.

Here’s where you can still pick up free meal kits this summer:

Bellows Falls Union High School (WNESU)

Wednesdays, 1:00–3:30 PM

Brattleboro Union High School (WSESU)

Thursdays, 12:00–3:00 PM

Leland & Gray or Jamaica Elementary (WRED)

Thursdays, 12:00–3:00 PM

A heartfelt thank-you to the school food service teams, community volunteers, and local producers who continue to make this program possible. This work ensures that every child in our communities has access to nutritious meals this summer. We believe that is something worth celebrating!

Bellow Falls Union High School staff attend Northeast Farm to School Institute

In June 2025, a team from Bellows Falls Union High School, including staff and a local community member, attended the Northeast Farm to School Institute (NFTSI) kickoff event at Shelburne Farms in Vermont.

Photo courtesy of Shelburne Farms

This marks the beginning of a year-long professional development journey to expand what the school offers to its students and local community.

Organized by Vermont FEED, the Northeast Farm to School Institute brings together educators, food service professionals, school administrators, and community advocates. Through dynamic speakers, interactive workshops, and tailored coaching, the program helps teams build effective, sustainable Farm to School programs that benefit students, schools, and local communities.

The Bellows Falls team is enthusiastic about bringing fresh, engaging experiences to their students in the coming school year. Their vision includes integrating Farm to School concepts with the Vermont Harvest of the Month program—a statewide initiative that highlights seasonal, locally available foods each month through recipes, posters, and classroom resources.

“Farm to School is about helping students make meaningful connections between what they eat and how it affects their health, the environment, and their local economy,” said one team member. “It’s education that goes beyond the classroom.”

During the four-day kickoff event, the team participated in a wide range of sessions. Workshop offerings included curriculum planning, planning school gardens, student-centered taste tests, composting and recycling in schools, cooking with students, and even creative arts like printmaking with natural dyes.

Photo courtesy of Shelburne Farms

As the new school year approaches, the Bellows Falls team is ready to continue the work. They are committed to making the effort a collaborative one—welcoming students, staff, and community members to be part of the conversation and the hands-on work of building a thriving Farm to School culture.

With this foundation laid, Bellows Falls Union High School is poised to not only enhance student learning but also strengthen ties between the school and the local food system.

Attendees of the Northeast Farm to School Institute. Photo courtesy of Shelburne Farms

Written by: Adelaide Petrov-Yoo

From Garden to Storefront: BUHS Launches a Hands-On Culinary Program

Brattleboro Union High School is launching a new initiative that combines career readiness, academic credits, and community service. The pilot program, called CAVE Kitchen (Culinary Agriculture Vocational Education), offers students a therapeutic work environment while they learn both soft and hard employment skills.

Unlike traditional classroom settings, CAVE Kitchen allows students to earn academic credit while working in a commercial-grade kitchen and operating a storefront.

Last week, students led a tour of the facilities, which include a flourishing kitchen garden, a fully equipped commercial kitchen, and a campus storefront named The Daily Bear. The atmosphere was professional: students were familiar with the kitchen, moving with purpose, chopping garlic scapes, loading industrial dishwashers, and preparing home-made snacks like chocolate zucchini snack cakes.

Beyond cooking, the program immerses students in the full scope of food service. Students handle everything from menu planning and knife skills to ordering supplies and maintaining a clean work environment. Students also help grow and harvest produce in the garden, giving them a seed-to-sale understanding of food systems.

Importantly, CAVE Kitchen builds technical skills and a place to learn and practice soft skills crucial to long-term employment success; professional communication, teamwork, punctuality, and problem-solving.

A student-run store, The Daily Bear, will be open to the 45 businesses located on the Winston Prouty campus, as well as to the general public. It will offer grab-and-go meals, providing a convenient, on-site food option, and valuable business experience for students.

Winston Prouty “campus tenants…are impressed by the garden and are enthusiastic about the prospect of being able to pick up a drink and snack right on campus someday soon,” says Emily Webb, campus director of Winston Prouty Center.

Chloe Learey, executive director of Winston Prouty Center, said she is “inspired by The Daily Bear. It is a great example of what we hope to accomplish on the Prouty campus, offering space for creative, innovative opportunities that help strengthen and connect our whole community.”

This project is a part of a four-year University of Vermont Extension 4-H grant called Youth Innovators Empowering Agriculture across America (YEA), funded by the USDA. There are four other projects in New England funded by this grant, all focusing on improving access to 4-H experiential learning opportunities.

Unlike many grant-funded programs that vanish when funding ends, CAVE Kitchen is built for sustainability. Proceeds from The Daily Bear will be reinvested to support the continuation of the program.

CAVE Kitchen’s value goes beyond being just a culinary class, it’s also a therapeutic, empowering environment that prepares students for real-world employment, while building confidence and life skills. With built-in sustainability and strong community ties, this program could become a model for other school districts seeking creative, meaningful ways to prepare students for life after graduation while also meeting students where they are.

Read more about the program in the Brattleboro Reformer’s July 25th, 2025 article on the student’s successes.

Written by: Adelaide Petrov-Yoo

Growing Together: a Farm to School Community of Practice

A seed was planted in the fall of 2024 by Mandy Walsh, school librarian and experienced Farm to School (FTS) educator at Westminster Center School. She put forward the idea to strengthen the community of educators in southern Vermont who are working towards Educating for Sustainability and strengthening Farm to School education in their schools.

Food Connects staff, with support from a grant from the Vermont Agency of Education and the Vermont Farm to School and Early Childhood Network, were able to nurture that seed through a 6-month Community of Practice group for educators, and the harvest has arrived!

Here’s a summary of the growth of this inspiring peer-to-peer professional development program.

After several planning sessions between Mandy, Jody Hauser (school librarian and FTS champion at Central Elementary School in Bellows Falls), Kris Nelson (FTS Program Director at Food Connects) and Sheila Humphreys (FTS Lead Coach at Food Connects), we launched the 6 month discussion series in January 2025.

Over the past 6 months, 12 local educators from 3 different school districts have participated in these monthly discussions. Topics, chosen by the educators themselves, and included:

January: Connecting Expeditionary Learning (EL)with Sustainability and FTS

February: Composting and Vermiculture

March: Family and Community Engagement in FTS Programs

April: Integrating Vermont’s Harvest of the Month Program with EL and FTS

May: Garden and Greenhouse Tour, Westminster Center School

June: Garden and Outdoor Classroom Tour, Academy School

The Community of Practice Model allowed the group to engage in the process of collective learning about a topic that inspires all of them. By sharing their knowledge and experiences with each other, asking questions, and inviting guest presenters to speak to the group on specific topics, all participants benefited from the opportunity to improve their teaching practices. They also were able to strengthen relationships with like-minded educators in neighboring districts and create a shared repertoire of resources.

In addition to curriculum connections, this group of educators also discussed ways to increase family engagement in their programs, from harvest dinners to community work days to school based farmer’s markets. They discussed problems with school composting systems, and brainstormed solutions to better educate their school communities about composting, including working in partnership with Windham Solid Waste Management District’s Education Coordinator, Alex Lacy and doing hands on composting initiatives like vermiculture in classrooms and onsite composting for garden waste.

They explored ways to connect the vibrant Vermont Harvest of the Month Program, which is a great entry point for new schools that are just beginning their Farm to School programs as well as a lasting resource for thriving FTS programs, into EL curriculum and explored best practices for taste tests in schools.

The last 2 sessions were held in-person, on-site, in school gardens at Westminster Center School and Academy School.

We look forward to watching how this inspiring community of educators continues to grow and blossom over time!

Student Power on Full Display at the 2025 FEAST Conference

When was the last time a teenager planned something for you? Was it a meal? A vacation? It can be hard for adults to hold back the “helpful suggestions” or comments when supervising a student project. However, when we stand back and let youth lead, the results can blow you away. This month, I had the pleasure of being an adult participant at a youth-led conference, stepping back to witness Vermont students shine.

In 2025, for the third year in a row, five students from across Vermont met online every Monday for months to plan a youth-organized conference with keynote speakers and workshops.

The result was the third annual FEAST conference (Food Education And Sustainable Thinking), hosted at American Flatbread at Lareau Farms in Waitsfield, VT. This annual event is a program of the Vermont Farm to School and Early Childhood Education Network and made possible thanks to generous donations and funders of the Network.

It was planned and hosted by five students from high schools across Vermont: Champlain Valley Union High School in Hinesburg, Harwood Union High School in Duxbury, Leland and Gray High School in Townshend, and Middlebury Union High School.

Video of 2024 FEAST activities

This year the student leaders chose to invite a keynote speaker from Migrant Justice, a local Vermont organization advocating for workers’ rights in Vermont.

FEAST’s youth planners identified and invited collaboration with an important ally, Migrant Justice, connecting our students to real-life experiences in Vermont’s farms and food systems. Migrant Justice connects community members with farm workers.

Enrique Balcazar spoke about his experience working on dairy farms in Vermont. For any students wondering “what do I do?” or “how do I help?” to strengthen our local food system, Enrique shared the steps that his organization took when fighting for Milk With Dignity, to demonstrate how to build support from within a community and also how to persist with one’s goals even when there are setbacks..

In the case of the Milk With Dignity campaign, first Migrant Justice made agreements with farm owners who would promise to protect good working conditions for their employees. They then contacted Ben and Jerry’s to ask that they only buy from farmers who were proven to respect workers rights. Finally, when Ben and Jerry’s wasn’t interested, they rallied, collected signatures, and gained support until Ben and Jerry’s changed their mind. Now Migrant Justice is asking Hannafords to join the Milk With Dignity program and rallying support for this movement.

After the keynote, attendees joined student-run workshops.

These workshops were planned and run by students! Many of these workshops featured hands-on activities and take home projects, like succulents, mushroom grow-kits, and letters to state representatives. 2025’s workshops were:

Food Systems of the Future & Mushrooms by Pacem School

Legislative Advocacy by Harwood Union High School Youth Lobby

Creamery Considerations & Cheese Tasting by North Country Career Center

Micro-goat Dairy Farming by White River Valley High School

AI, Climate Change, and Water Usage by Champlain Valley Union High School Sustainability Club

Sustainable Practices in Maple Sugaring by Harwood Union High School

Farm Tour and Work by Lareau Farm

Tortilla-making from Scratch by Montpelier High School

There were also two workshops for adults. These helped create youth spaces free from adult oversight, while simultaneously providing engaging workshops for the supporting adults. Those workshops were:

“Community Based Learning for High School students” by Jessa Harger, Leland and Gray High School

“Felting 101” by Elyse Perambo, Green Mountain Farm to School

As a closing activity, students made seed-bombs and took home free seeds. It was lovely to see students motivated, excited, and happy. Many look forward to joining again next year. If you are interested in being part of the planning committee for FEAST 2026, email adelaide@foodconnects.org.

Sunny Side Up: NewBrook’s Farm & Field Day Delights

The sky was blue and spirits were high at NewBrook Elementary’s annual Farm & Field Day: a joyful celebration of hands-on learning, community connection, and all things Farm to School. Students roared through a vibrant rotation of activities in multi-age teams proudly named Kale, Squash, Carrot, and more.

Each station offered a new way to explore the natural world.

Students raced to sort compost, recycling, and trash in a waste relay with Alex from Windham Solid Waste. Chris guided curious eyes through the many treasures to be foraged and found in the forest, including cool skulls and mushrooms.

Tails wagged and hearts melted as Cindy from Monadnock Therapy Pets introduced students to a friendly therapy dog. Students also met rabbits and their farmers, Seren, Rick, and Cedar of Giant Journey Farm, and learned what it takes to raise animals with care.

Nearby, Shiloh led fiber arts activities and brought along a lovable goat named Vax, who quickly became a crowd favorite. Kids crafted their own environmental pins with Suzanne and Lucia Paugh, pedaled their way to fresh smoothies on the bike blender, and baked up fun in the school’s pizza oven.

At the Harvest of the Month tasting table, hosted by Food Connects, deviled eggs took center stage in celebration of eggs as May’s highlighted crop.

“Cheese” group visits Harvest of the Month table.

Kids eagerly lined up, half for the chance to build their own deviled eggs, half excited to share everything they’d learned about birds, eggs, and even ostriches.

They could hardly contain their excitement, and when it came time for questions, hands shot up:

“Can I eat a robin’s egg?”

“I know how to poach an egg!”

“Sunny side is my favorite!”

But probably the most asked question was:

“Can I have another one?”

One student even asked for a handful of chives, and happily munched them like candy while waiting his turn to crush eggshells for compost, the follow-up activity that demonstrated how to make your own calcium additive for the garden.

At its heart, Farm & Field Day is a celebration of connection.

It brings together students, families, farmers, educators, and community members to highlight how farm to school programming touches every part of our lives, from the food on our plates to the ecosystems around us.

Devan Monette and Amy Duffy, Newbrook Garden Coordinator

With the sun shining down on us, nothing was more clearly illuminated than the power of food to bring a community together. Whether it’s sharing a slice of wood-fired pizza, learning about the animals that call our neighborhood farms home, or laughing over the smear of yolk on a smiling kid’s nose as they scarf down a deviled egg, food has the power to teach, to heal, and to connect.

NewBrook Elementary celebrates the end of Farm and Field Day by singing the Vermont state song with Principal Scotty Tabachnick.

And at schools like NewBrook, where students get the chance to grow it, cook it, and share it with their classmates, families, and the greater community throughout the year, we witness the kind of education that sticks. It’s the kind of learning that builds confidence, encourages curiosity, and plants the seeds of lifelong wellness.

by Devan Monette